The 77th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp is Thursday, Jan. 27. It is also International Holocaust Remembrance Day, a day of memorial for the six million Jews and 11 million others killed by the Nazi regime and its supporters during World War II.

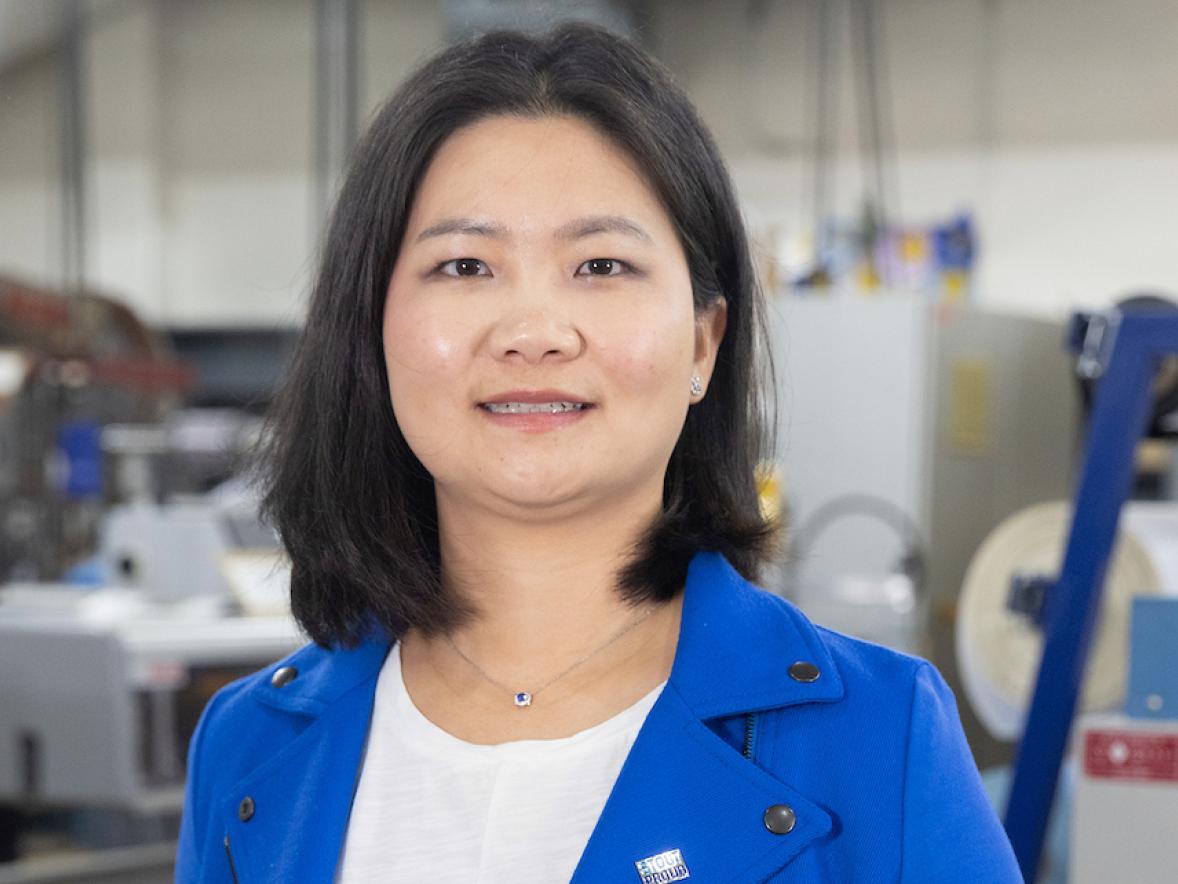

Jacob Hellman, lecturer and professor of public speaking in UW-Stout’s English, philosophy and communication studies department, is a third-generation Holocaust survivor.

He will share his family’s story from 5 to 6 p.m. on Wednesday, Jan. 26, in the Memorial Student Center, Ballroom A. The event is free and open to the public. Attendees can register for the in-person event on CONNECT or attend virtually on Teams Live.

“My family’s story enriches UW-Stout’s story,” he said. “I want to spread a message of tolerance to everyone and add to our university’s tapestry and diverse community.”

His grandparents Richard and Betty Hellmann – Jacob’s father, Stanley, changed his name to Hellman – often shared their experiences during Kristallnacht, of the violence they witnessed as they fled their home and of their journey to the United States. Betty told their story many times to school groups and was interviewed by the Spielberg Foundation.

Jacob always knew his grandparents’ story, and as he grew older, he learned more details of their attempt to leave Germany prior to World War II. Growing up in the Baltimore area, where there is a large Jewish population, Jacob knew many Holocaust survivors and descendants who knew their own family’s stories.

But coming to the Midwest and teaching at a smaller Wisconsin university, Jacob thought, “Maybe most UW-Stout students haven’t heard a Holocaust survivor story before.”

The story that follows is only a portion of Jacob’s family’s experience. For more details, visit Stanley’s article, “Kristallnacht: a Family’s Saga,” recently published in WhereWhatWhen.com, a monthly Jewish periodical in the Baltimore area.

Preparations to leave Germany

For six centuries, Jacob’s grandfather’s family had lived in Gunzenhausen, a Bavarian town of about 16,000 people, 35 miles southwest of Nuremberg, Germany.

Jacob’s grandfather, Richard, was born in the family’s house on Kirchestrasse, or Church Street. His grandmother, Betty, grew up in Markt Berolzheim, a nearby village.

Richard and Betty married in 1936, and their daughter, Ruth, was born the following year. The family lived in the house on Kirchestrasse, along with Betty’s mother, Helene, Richard’s brother Henry and a boarder, known as Mr. Mosner.

In the mid-1930s, tens of thousands of Jews emigrated from Germany for fear of persecution. Until the Germans invaded Russia in June 1941, it was possible to leave Germany, but there was a quota regulating the number of Germans emigrating to the U.S.

To register his family for emigration, Richard traveled 110 miles to the nearest U.S. consulate in Stuttgart. When he arrived, he realized Helene hadn’t signed her application, and he had to make a second trip to Stuttgart. Each family member received a number on the emigration waiting list, with Helene having a higher number, further down the list.

To prepare for the move, the Hellmanns also hired an English tutor, a Jewish woman from Furth, a suburb of Nuremberg. The tutor came to Gunzenhausen once a week and either took the train back to Furth in the evening or spent the night at the Hellmanns.

And so, on the night of Kristallnacht, November 9, 1938, there were seven people asleep in the house on Kirchestrasse.

Kristallnacht

They awoke to shouts of “Juden raus – Jews, come out.” Nazi soldiers and marauders flowed down Kirchestrasse. Mosner, the boarder, risked his life by going to the window and shouting that no Jews lived there.

As Jewish businesses, homes were ransacked, the Hellmanns decided to flee. Richard grabbed some cash and, in the confusion, left the house in his bedroom slippers. The family had forgotten that the English tutor was sleeping in the house, and they fled without her.

As the family left through the rear of the house to the garage, they could hear the sounds of furniture and glass being smashed in the front. As Richard drove out the gate, looting Nazis emerged from the house. One of the Nazis, carrying a broken table leg, jumped onto the running board of the car and smashed a window. Richard hit the accelerator, and the car bolted forward out of the driveway onto the street. The Nazi soldier lost his balance and fell to the ground.

Richard did not slow down. The family left Kirchestrasse in the dark of night with nothing but the clothes on their back, while Jewish homes, business and synagogues all over Germany were set on fire.

For days they drove to different cities across Bavaria, seeking refuge with friends and family, eventually finding shelter in Nuremburg. Richard and Henry knew they could not return home – they’d heard the Jewish men of Gunzenhausen were arrested and sent to the concentration camp at Dachau.

Return to the house on Kirchestrasse

Weeks later, the Hellmanns decided to try and retrieve some of their possessions from their home. Since Betty was young and blonde and not wanted by the Nazis, it was decided she would see if anything could be recovered. To blend in further, she took 16-month-old Ruth.

Nervously, Betty boarded the train from Nuremburg to Gunzenhausen. When she arrived, the townspeople stared at her – it was well known that the Hellmanns had fled and not returned.

When she got to the house, she saw that everything had been destroyed. Her siddur, or prayer book, had several knife stabs through the cover, with deep cuts through nearly every page. The only thing that remained intact was a guitar standing in a corner. Betty picked up the guitar and cracked it across her knee. Now everything was broken.

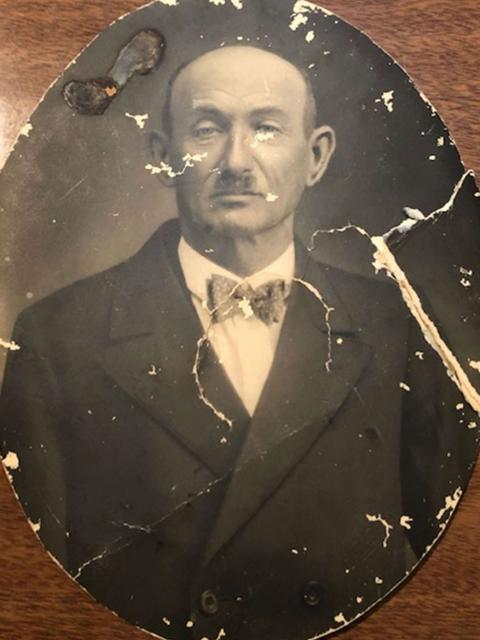

She retrieved her siddur, photos that had been torn, including one of her father, Salomon, clothing, books and documents – whatever she could carry by hand to the train returning to Nuremberg.

Betty braved the trip to Gunzenhausen several more times over the next few months, with suitcases to recover what she could.

On their way to Belgium

In August 1939, after 13 months of waiting, living under a curfew and blackouts, Richard, Betty and Ruth were notified by the emigration office that their numbers had been reached. They could leave Germany. Helene and Henry still had to wait.

They were limited in what they could take with them. Betty sewed some jewelry into Ruth’s teddy bear. But Helene insisted that Betty remove the jewelry, as she could be arrested for illegal smuggling. So, Betty ripped the teddy bear open and hid the jewelry in the rafters of the attic of the apartment building where they were staying.

Before dawn on Sept. 22, Richard, Betty and Ruth took a taxi to the Nuremberg train station. They were only allowed out after curfew because of their train tickets.

When the train reached the Belgian border, all passengers and luggage were inspected by Nazi border guards. Because of Betty’s blonde hair, the woman searching her thought she wasn’t Jewish and asked why she was leaving Germany with a Jewish man, meaning Richard, who had darker hair and skin tone. Betty said that, indeed, she was also Jewish, and what had been a routine examination turned into an invasive search.

When the searches concluded, everyone returned to the train, and as it crossed the border into Belgium, the Hellmanns felt free for the first time in years. Belgian towns were filled with light as they passed. Belgium would not be overrun by the Nazis until the following spring.

On the anniversary of Kristallnacht

The Hellmanns arrived in Antwerp, Belgium, on Kol Nidre night, and Richard was invited by a group of men to synagogue for the service on the eve of Yom Kippur. Having lived 6½ years under the Nazi regime, he was overwhelmed by the experience, and despite having eaten practically nothing since leaving Nuremberg the day before, Richard fasted for the entire Yom Kippur.

The Hellmanns purchased tickets to travel from Antwerp to New York on the Veendam, a ship of the Holland-American line. For the next seven weeks, they lived in the Hotel Max at the expense of the shipping company.

On Oct. 28, 1939, the Veendam began its trans-Atlantic voyage. And on Nov. 9, the anniversary of Kristallnacht, it docked in Hoboken, N.J. The Hellmann’s took the train to Baltimore to begin the next chapter of their lives. They were joined by Helene in January 1940.

Henry flew to Spain in May 1941, before travel restrictions were enforced. On Aug. 7, 1941, he left Seville on board the Navemar, a cargo ship chartered by the American Joint Distribution Committee to transport Jewish refugees from Europe. This was the last large group of Jews to leave Europe. The ship’s capacity was a few hundred. More than 1,100 people crowded aboard the vessel. The ship reached New York on Sept. 12, 1941.

As Jacob continues to share his family’s experiences, he wants to positively contribute to the culture of social justice and believes “we need to combat messages of hate.

“We need to remember our roots as humans,” he said. “In our lifetime, the Holocaust will pass out of living memory. We need to preserve the memory and as a human society need to keep it alive, or we are doomed to repeat it.”

Jacob's presentation is co-hosted by UW-Stout's Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Office and the Involvement Center.