Jonathan Wheeler obtained his Bachelor of Fine Arts at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design in the late 1990s and later, received his degree in Art Education from UW-Stout. He studied a variety of disciplines including painting, photography, and drawing. But his main focus was sculpture because he appreciates the fluidity of the art-form.

“I am, at my core, a builder,” Wheeler said. “I am fascinated by the construction of artifacts that share this space with us. Sculpture allows me to incorporate all kinds of media in my works. I have an aversion to specialization which, as it turns out, is a good aversion to have as an art teacher.”

His affinity for building and aversion to specialization led Wheeler back to Stout to pursue his Master of Fine Arts in Design where he enjoys the cross-disciplinary setting of the program.

“I don’t feel pigeon-holed, locked into one track,” Wheeler said. “If I have a curiosity about a subject, which I’m prone to, I can explore that subject with the support of great educators.”

Inspirations in Filmmaking

Wheeler found artistic freedom within his Digital Cinema course with Professor Peter Galante.

“Professor Galante let me make what I wanted,” Wheeler said. “He gave me the validation I needed to pursue filmmaking which lets me use all the skills I love: painting, sculpture, and photography.”

Now completing a second Digital Cinema course with Professor Michael Heagle, Wheeler expanded his cinematic horizon. Professor Heagle opened up the act of filmmaking for Wheeler as a problem-solving exercise that engages all of my creative faculties; from storytelling to digital special effects and sound design.

“He encouraged me to lean into my interests as a filmmaker and has been a great source of inspiration for me,” Wheeler said.

A camaraderie between Wheeler and Professor Heagle stemmed from their shared interest in retro science-fiction films like Star Wars, Flash Gordon, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, and David Lynch’s Dune. Professor Heagle believes these films take up the mantle of fantasy.

“Our common interest in the visual effects and design of films enabled us to have a kind of geek shorthand,” Professor Heagle said.

Being a “voracious consumer” of all things science fiction, Wheeler’s art is also influenced by historical and current events. The future where humans are subjugated by machines is a common sci-fi trope, but for Wheeler there are echoes in real life.

“Vladimir Putin just told a group of University students that the country that leads in AI research will rule the world,” Wheeler said. “Our own culture in the U.S. blindly trusts data and algorithms over independent human thought.”

As an artist and educator, Wheeler finds this ideology troubling. He believes public schools focus and support STEM programs while art programs are cut or de-funded, encouraging students to become engineers rather than artists.

“Our culture is already taking the seemingly small, inconsequential steps that relegate more of our choices to machines that will lead to a future that I’m illustrating in my films,” Wheeler said.

In his newly released film, SPiN, Wheeler imagines one version of this future.

SPiN, a Surreal Space Opera

SPiN opens in a lush forest, possibly in early fall. Leaves are just beginning to turn. A child, dressed in a hooded monk’s robe, rain boots, and deer mask, is collecting stones and placing them in a satchel. Organic textures of mushroom, moss, fern, and damp wood fill the screen. These bits of nature are interrupted by concrete ventilation shafts and sewer grates seeping steam, reminiscent of George Pal’s The Time Machine.

The music is playful, technical and resonating. Birds sing nearby as the child walks down a path, peering skyward into the branches arching above, searching. What is the child seeking? A large mossy orb perched on a high branch, its plush surface accented by course pine needles. The child removes a stone from the satchel and pauses, hands enclosed around the stone as if reflecting on a sacred text before launching it into the canopy, knocking loose the mossy orb. It falls to the forest floor.

Collecting the orb, the child transfers it to a different part of the forest where a lone antler rests against a tree trunk. Leaves crunching under small feet, the child sets the orb on the ground, patting it gently like a delicate pet. The orb seems sacred. This is no longer a child at random play but instead has a much greater purpose. But, to what end?

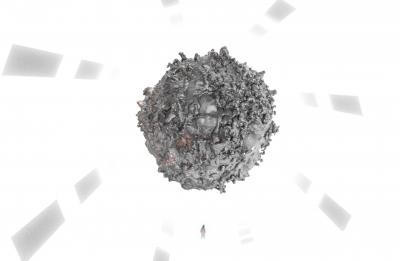

Cut to a dramatic scene change: an immense tube rotating in deep space, a metallic sphere like a rough lead ball looms in the darkness, a few distance points of light. A cosmonaut places an object on her control panel before lowering her visor and securing her helmet. The object is cast in shadow but appears to be an animal of some sort. A talisman for her mission? The music also changes with this new scene: sounds of nature and pleasant tones mutate into blasts of lasers, jets of air, and measured breathing. A sense of immense loneliness gives way, but the cosmonaut’s focus tells she is awaiting directives.

From here, there are many scene changes between the child’s activities and the cosmonaut’s perspective. The child uncovers a toy hidden in a log: a small wooden spaceship. The child secures a length of twine between the toy and the mossy orb. A tow-ship emerges from the tube in space. Within the tow-ship, the cosmonaut blasts off toward the metallic sphere. A cosmic connection between the two characters becomes apparent. Their actions, along with the collision of sound from both realms, foretells of a merging of worlds.

Entering a tunnel, the metallic sphere is engulfed in light. The child lowers the deer mask and rushes through the forest. With a hidden face, the child enters the tunnel from the opposite end. The metallic sphere descends. As if heated from within, the sphere begins to glow red-hot. Lowering the monk’s hood and removing the mask in an act of beatification, the child’s face is revealed again. With open arms and the hint of a smile, the child transcends to the sphere, engulfed in light. The mask falls to the ground.

The End. (Or, the new beginning.)

The Making of SPiN

The imagery in SPiN stirs thoughts of other worlds, the afterlife, and transcendence. Its many dual images cause reflection of meaning; youth versus adulthood, nature versus industry, silence versus sound, light versus dark, and freedom versus obligation.

“The best way to know something is to study its opposite,” Wheeler explained his use of dual images in SPiN. “Like in color theory, a viewer can be impacted more by a value if it’s sitting next to a contrasting shade or tint; so too can a concept be better illuminated by proximity to its contrast.”

“Picasso once said that every artwork is a self-portrait,” Wheeler said. “After two decades of being a grown-up, I have recently begun to explore the interests that I once held so dear as a child. My film represents the relationship between myself as a grown-up and the memory of my childhood. I hope the viewer gets an impression of change and metamorphosis.”

The metamorphosis of the characters in SPiN is very apparent and viewers build a deep connection with them, curious as to what they are doing, where they are going, and what will happen to them. Wheeler, too, is very invested in his characters and in the actors, themselves.

“When I write screenplays, I imagine who will play the characters,” Wheeler said. “It’s a big part of my process to put those faces I know to the roles I’m creating.”

For SPiN, Wheeler wrote the parts specifically for his wife and child. Including his family in SPiN was a meaningful experience for Wheeler.

“Between teaching and grad school, I get to spend precious little time with my wonderful family so writing them into my films is an important way for me to spend quality time with them,” Wheeler said.

As an artist, particularly as a sculptor, Wheeler was able to create his own props and sets. He uses sculpture to make worlds, to populate environments that exist in his imagination.

“These artifacts include props like the objects in SPiN or models like the spaceships and sets like the cockpit,” Wheeler said. “I built all of these in my 150-square-foot studio.”

Wheeler also created the music for SPiN using Garage Band. He was trying to convey a sense of 70’s sci-fi nostalgia to complement the contrasting scenes, blending into the background instead of distracting from the visuals.

The biggest challenges for Wheeler were creating the digital effects for SPiN. Wheeler spent hours working in After Effects that resulted in seconds of finished footage. He credits Professor Heagle as an asset in the creation of the digital effects and other production pieces.

“He lent me the cosmonaut suit which has put the production value up to a semi-professional level,” Wheeler said. “Cripes, that guy is awesome.”

While instructing Wheeler, Professor Heagle’s own storehouse of knowledge came in handy. Professor Heagle had been reading about the making of science fiction films since he was about ten years old. He really enjoyed being able to talk about things like lighting, depth of field, details on miniatures, shooting high-speed photography to eliminate wobble on objects that were toy-sized – all the tools that have been largely ignored in the rush to accomplish it all on the computer.

After the screenplay is written, the props, sets, and miniatures built, costumes acquired, footage shot, sound, and visual effects developed, the challenge of the editing process begins. What to keep, what is vital, what to cut? Audience perception is of paramount concern to Wheeler as a director.

“I don’t want to oversimplify the imagery because I believe my audience is pretty smart,” Wheeler said. “I want to keep the metaphors complex but not too confusing. My worlds have a logic, laws that are followed so the narrative is creative but not random.”

“When I shoot, I collect far more footage than I need so I really only use a small fraction for the final product,” Wheeler said. “Critique is essential at the rough-cut stage because I tend to fall in love with shots that are redundant or unnecessary; a trusted set of fresh eyes can tell me where to trim or cut. Syd Field, a renowned screenwriting teacher, says to ‘kill your darlings’.”

One of these darlings is the cosmonaut’s talisman, hidden in shadow. In the rough-cut, the talisman is shown in the light of the cockpit. It is clearly a red stag.

“The stag is a call-back to the child’s mask,” Wheeler said. “I was hoping to suggest a relationship between the adult and the child.”

SPiN was featured at Unspooled Film Festival, Tuesday, December 18, 2018.